Breaking the cycle of generational trauma through whole-person education

The partnership between constituents from the Pacific Union (and beyond) and Holbrook Indian School (HIS) has empowered Native American students to overcome distinctive barriers to learning through a whole-person approach.

Many students attend HIS because they weren’t succeeding at their previous schools. This is often due to traumatic events they’ve experienced or their basic needs not being met, such as the need for prescription eyewear, concerns over where their next meal is coming from, or the inability to travel to the dentist to relieve an aching tooth. The effects of generational trauma also impact a child’s ability to succeed.

HIS is more than just an institution for learning. It is—in a genuine sense—a home away from home. HIS provides students with healthy meals, personal care items, transportation to and from school when needed, trips for health care appointments, counseling, and assistance with other basic needs.

Here are the top five ways that friends of HIS have helped to empower Native children and youth through their partnership with the school.

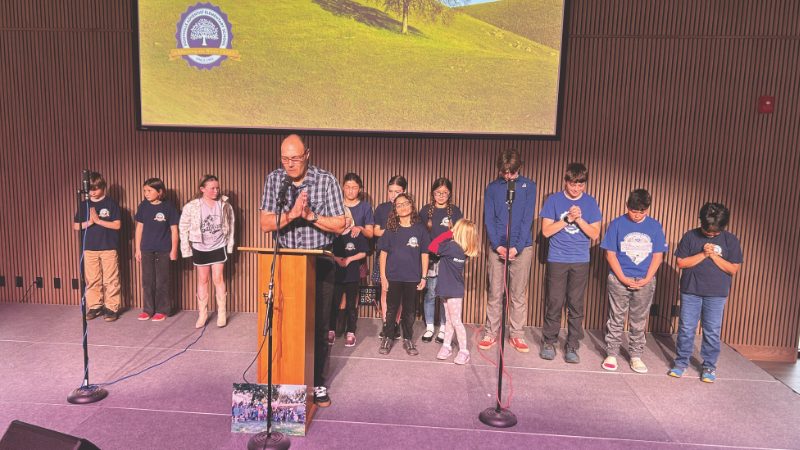

Outdoor School – A Love to Learn and Explore

Last school year, Kaiss attended HIS for the first time. The Outdoor School trip was also his first time going to Grand Canyon National Park. What was his reaction? “If I had the chance to do more outdoor activities, I would go out and explore more,” he said.

Kaiss and other students spent seven days camping and learning at the Grand Canyon. During that time, they participated in several classes of their choice. These outdoor-focused lessons not only taught them specific skills but also gave them a new perspective and appreciation for learning. “A week of doing school at the Grand Canyon opened my eyes to see that there is so much more than what I see on a daily basis,” Kaiss said.

You can watch Kaiss’s Outdoor School experience in the short film “Class by the Canyon” at HolbrookIndianSchool.org/outdoor.

Feeding Our Students – Healthy and Nutritious Meals

Providing students with healthy, nutritious meals is a priority at HIS. Many students come to the school with nutritional deficits that affect their ability to learn.

In March, a 2006 graduate, Jovannah Poor Bear-Adams, returned to HIS as a special guest speaker for its 75th anniversary celebration. During her speech, she shared how, as a child, she would swallow air in an effort to stop her hunger pains. She spoke about a time when her family would go to the grocery store on “food stamp day” and fill their shopping carts with all the snacks and French fries they could. “We ate like junk food kings for a week,” Poor Bear-Adams stated, “and then the rest of the month, we’d go hungry,” an unfortunate result of poverty.

Poor Bear-Adams described how surprised she was when she came to HIS and saw that students received three healthy meals a day. That was something she only saw on TV. She credits HIS for her ability to provide her children with healthy, nutritious meals.

Meeting Students’ Basic Needs

There are often times when HIS students have basic needs that are not being met. For example, we had two young sisters come with only a couple of pairs of pants and a few shirts between them. They only had one pair of shoes each, and they didn’t fit well. They didn’t have a jacket or bedding. Unfortunately, this is not uncommon.

Often students need glasses. Although Indian Health Services provides one pair of glasses to each tribal member per year, the services are sometimes backed up for months. Since these students can’t do their school work without glasses, we need to help provide them.

Then there are times when families can’t afford gas or don’t have reliable transportation to bring their children to and from school during breaks. Most students live a minimum of two hours from HIS. Staff members provide students with transportation. These are just a few examples of how our partners make a tremendous difference in the lives of our students.

Outdoor School at Holbrook Indian School

Counseling

Traumatic life events prevent students from focusing in the classroom. Students have the option to go to Indian Health Services for counseling; however, that takes a lot of time away from their classes, and often a student’s ability to cope with his or her specific experience can’t be addressed in this setting.

HIS established an on-site counseling program in 2014. Since then, it has transformed the lives of a number of students. HIS licensed clinical counselor Loren Fish described how one student was demonstrating severe depression and anxiety and scored extremely low in self-worth. “Practically, within three months of counseling, that student was able to show major improvement,” Fish said.

Most recently, students who were on the school bus during a deadly August 28 accident reported flashbacks, as well as nightmares. Two students were willing to anonymously share the impact counseling had in helping them work through the trauma. In terms of anxiety levels and ability to cope, on a scale of 1-10, “I went from being at 8 to now being at 0,” one student said. Another student shared that they appreciated that this kind of help was available after experiencing this traumatic event.

Since the counseling department was instituted, there has been an increase in students on the honor roll, and the general culture on campus has improved. The impact of the counseling department over the years has more than made up for the investment.

Tuition – A Life-Defining Opportunity

A majority of HIS students’ families are at or below the poverty level and are not able to afford tuition. The majority of the cost for a student to attend HIS is supported by the school’s partners. This enables Native youth, who would otherwise fall through the cracks, to have access to an accredited, Christian education in a safe, healing environment—regardless of their ability to pay.

The effects of generational trauma have caused many Native youth to grow up in broken families. In order to break the cycle, they need opportunity. Consider the value of whole-person education for one youth like HIS senior Quentina.

Quentina came to HIS when she was in the fifth grade. Her lack of academic focus reflected her unstable circumstances. “I grew up with my grandma,” Quentina reflected. “My father was not there for me physically, and my mother was not there for me emotionally. The other kids bullied me a lot whenever the teachers weren’t looking. I always got caught reacting to the teasing and got sent to the principal’s office daily.”

Quentina's frustrating experience with school gave her a dislike for reading and learning. “One time I told the teacher, ‘Just give me an F!’” she said. Despite her contempt for learning, Quentina said she loved being at HIS: “I liked staying here. Home was a bad atmosphere. It gave me suicidal thoughts from all the negativity.”

Through intervention and coaching from her mentor, Quentina’s relationships with her peers improved. Through patient help from teachers, she grew an appreciation for reading and learning. Finding something at HIS that was missing at home, Quentina would stay on campus for the entire summer break.

Over the past four years, Quentina has been on the honor roll. There was a time, however, when circumstances almost forced her to stop attending HIS. “My grandma was going to withdraw me from HIS because of the cost of tuition and travel,” Quentina recalled. “I was going to have to change schools, and the day I was waiting for my grandma to come and get me, I was sitting on the side of the curb, ready with my withdrawal forms, and Mrs. Adams [former vice principal] asked where I was going. After I explained the situation, she said I didn't need to withdraw because the school would help.”

Quentina reflects very positively on this life-defining moment. She was able to remain at HIS and has had significant academic and emotional growth since then. Many former and current students like Quentina benefit from the whole-person approach to education at HIS.

____________________

By Chevon Petgrave and Diana Fish