Many prominent Adventist leaders held views on slavery similar to those of Mrs. White. Through the Civil War years, such revered names as James White, Uriah Smith, and J.N. Andrews used the pages of the Review and Herald to attack laggards who did not endorse the emancipation position. An example is Uriah Smith's explicit criticism of President Lincoln. Tacitly acknowledging his own position to be radical, Smith censured the president for “following his present conservative, not to say suicidal, policy.”1 With emancipation still not official, Smith's hostility toward Lincoln was unrelenting.

“He has to stand up against the 'enthusiasm for freedom' which reigns in nearly twenty millions of hearts in the free North, and against the prayers of four millions of oppressed and suffering slaves. If he continues to resist all these, in refusing to take those steps which a sound policy, the principles of humanity, and the salvation of the country, demand, it must be from an infatuation akin to that which of old brought Pharaoh to an untimely end.”2 Smith could not know that Lincoln's assassination would, in retrospect, make his analogy downright grisly.

When the North was losing major battles, Mrs. White complained because “the rebellion was handled so carefully, so slowly.”3 Later, when the North was consistently winning, her husband, James, jubilantly wrote in the Review that “appropriate retribution seems to be at last overtaking the fearfully guilty parties who have for long years held multitudes of their fellow beings in bondage.”4

Introducing a reprinted news article about the exploits of former slaves, now in the Union Army, who pursued slave owners into North Carolina swamps, Elder White asked, “What could be more appropriate than that the slaves themselves should be the instruments used to punish the merciless tyrants who have so long ground them to the dust.” He was convinced that “Justice, though seemingly long delayed, is nevertheless following with relentless steps upon the heels of the oppressor.”5

In the forefront of Reconstruction

After the war, former abolitionists were in the forefront of Reconstruction. Such men as Thaddeus Stevens in the House of Representatives, Charles Sumner and Benjamin Wade in the Senate, and Edwin Stanton in the Cabinet came to be known as radical Republicans because they “seemed bent on engineering a sweeping reformation of southern society.”6

A recent history of the period insists that idealism was part of the motivation for Reconstruction and that “a genuine desire to do justice to the Negro, then, was one of the mainsprings of radicalism.”7 Radical senators and congressmen led in passing civil rights laws to ensure that Blacks would be able to vote and enjoy full civil liberties. Some radicals went farther. “They believed that it would be essential to give the Negroes not only civil and political rights but some initial economic assistance as well.”8

It is interesting to note that during the height of Reconstruction, 1867-1877, quotations in the Review concerning national affairs seem to have been taken exclusively from well-known, radical Republican publications. The attempt to impeach President Andrew Johnson was reported in detail.9

More significantly, when Mrs. White later addressed herself to the needs of the South, she lamented the miserliness and briefness of the government's concern for the emancipated Black man. She endorsed the humanitarian ideas of the most progressive wing of the radical Republicans—those who felt an obligation to help the Black man politically, legally, and economically.

“Much might have been accomplished by the people of America if adequate efforts in behalf of the freedmen had been put forth by the Government and by the Christian churches immediately after the emancipation of the slaves. Money should have been used freely to care for and educate them at the time they were so greatly in need of help. But the Government, after a little effort, left the Negro to struggle, unaided, with his burden of difficulties.”10

Undoubtedly, the “little effort” Mrs. White commended took place during the brief period from 1867 to 1877 when Reconstruction governments included Blacks, and some improvement was achieved in education, medical care, and welfare. She may also have referred to activities of the Freedman's Bureau. Organized and funded by a federal government dominated by radicals, it operated for only four years, until 1869. During that time the bureau gave medical care to a million people, spent $5 million for Black schools, supervised labor contracts for Black workers, and administered special courts to protect freedmen's civil rights.11 Mrs. White felt more should have been done, but Reconstruction ended too soon for the radicals to accomplish their sweeping reforms.

Within a little more than a decade after the Civil War, eight of the Southern states had voted out of office political leaders supporting radical Republican policies. In the elections of 1876, Democrats claimed victory in the remaining three states of the Confederacy: South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. The spring of the following year, President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew the last federal troops from the South. Reconstruction had ended. The Republican coalition of Blacks, Northern carpetbaggers, and White Southern turncoats had lost its dominance. Southerners called the new era “Redemption.”

Some persistent comparisons between Mrs. White (and other Adventist writers) and abolitionists and radical Republicans may leave the impression that Adventists merely adopted the outlook on national problems they found around them—that their religion had little to do with their views on social and moral issues. But this is far from the truth. If anyone had told the founding fathers of our denomination that their attitudes toward race had nothing to do with their theology, they would have shaken their heads in disbelief. For Ellen and James White, Uriah Smith, and J.N. Andrews, proper attitudes toward race relations were part of a true understanding of the Bible and its doctrines.

Slavery and prophecy

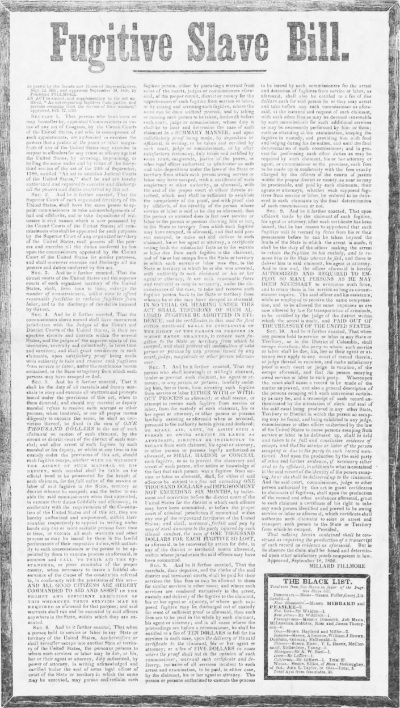

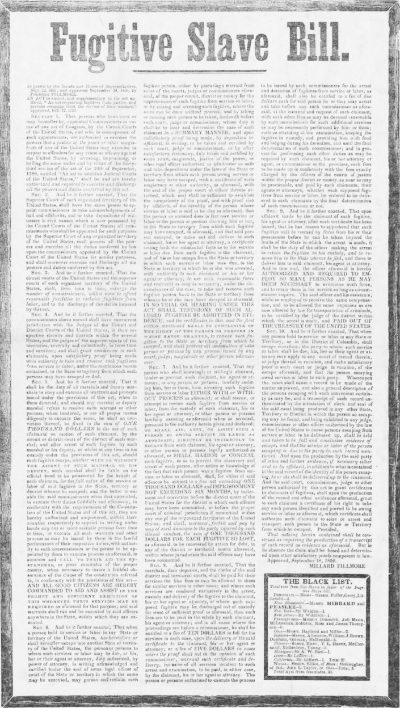

Emancipation was an official fact Jan. 1, 1863. For the next three months, 12 issues of the Review began with front-page excerpts from Luther Lee's Slavery Examined in the Light of the Bible.12 The book went through controversial texts in the Old and New Testaments, arguing strenuously that the Bible, far from condoning slavery, condemned it.

When the laws of men conflict with the word and law of God, we are to obey the latter, whatever the consequences may be. The law of our land requiring us to deliver a slave to his master, we are not to obey; and we must abide the consequences of violating this law. The slave is not the property of any man. God is his rightful master, and man has no right to take God's workmanship into his hands, and claim him as his own.

Both Uriah Smith and James White related slavery to prophecy. Just as the United States was divided into two camps, so the lamb in Revelation 13:11 had two horns. Oppression of Blacks in America was more significant evidence that the beast in Revelation 13 was the United States. Revelation describes a beast that looks like a lamb but speaks like a dragon. James White made the application.

“Its [United States'] outward appearance and profession is the most pure, peaceful, and harmless, possible. It professes to guarantee to every man liberty and the pursuit of happiness in temporal things, and freedom in matters of religion; yet about four millions of human beings are held by the Southern States of this nation in the most abject and cruel bondage and servitude, and the theological bodies of the land have adopted a creed-power, which is as inexorable and tyrannical as is possible to bring to bear upon the consciences of men. Verily with all its lamblike appearance and profession, it has the heart and voice of a dragon; for out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh.”13

Uriah Smith pointed to the “white-washed villainy of many of the pulpits of our land,” pulpits supporting slavery—evidence that “the dragonic spirit of this nation has of late years developed itself in accordance with the prophecy in Rev. xiii, 11.”14 Far from being a purely secular concern, Adventists thought race relations were intimately involved with a proper understanding of prophecy and last-day events.

Mrs. White also saw slavery as one of the signs of the times. She cited the defense of slavery by ecclesiastical institutions as proof that churches in America were part of apostate Babylon. “God will restrain His anger but a little longer. His anger burns against this nation, and especially against the religious bodies who have sanctioned, and have themselves engaged in this terrible merchandise.”15 God will remember the suffering slave and others who are oppressed. “The names of such are written in blood, crossed with stripes, and flooded with agonizing, burning tears of suffering. God's anger will not cease until He has caused the land of light to drink the dregs of the cup of his fury, and until he has rewarded unto Babylon double.… All the sins of the slave will be visited upon the master.”16

It would have been possible for Adventists to have opposed slavery, seen its evil as one of the signs of the end, and still not preached equality between Blacks and Whites. By the time of the collapse of Reconstruction and the birth of Redemption, when Mrs. White launched her appeals for the Southern work, even radical Republican papers assumed the inferiority of the Black man. “It was quite common in the 'eighties and 'nineties to find in the Nation, Harper's Weekly, the North American Review, or the Atlantic Monthly Northern liberals and former abolitionists mouthing the shibboleths of white supremacy regarding the Negro's innate inferiority, shiftlessness, and hopeless unfitness for full participation in the white man's civilization.”17 During this same period of the eighties and nineties, Mrs. White was adamant: Blacks and Whites are equal.

In addition to eschatology, or the study of last-day events, Mrs. White based her discussion of race on two other doctrines: redemption and creation. Christ's atoning and reconciling work meant that all men were saved, and none were more saved than others: “Christ came to this earth with a message of mercy and forgiveness. He laid the foundation for a religion by which Jew and Gentile, black and white, free and bond, are linked together in one common brotherhood, recognized as equal in the sight of God.”18 For Mrs. White, Christ had brought humans into a new relationship where each was equally related to Him. Christians, therefore, must look on other Christians as equals.

But what about those who were not Christians? If men were not converted, if they were not within the brotherhood created by Christ's redeeming life, could they properly relate as superior to inferior, master to slave? “No,” was Mrs. White's emphatic response. The doctrine of Creation prevents it. God wants Whites who relate to Black persons to remember “their common relationship to us by creation and by redemption, and their right to the blessings of freedom.”19 Elsewhere she insisted that “man is God's property by creation and redemption.”20

It is significant that Mrs. White did not support equality simply on the basis of redemption. Even if men were unconverted, the doctrine of Creation means that all humans, whether they acknowledge Christ or not, belong to God. Where people's equality and freedom are violated, it is not God acting, but humanity's sinful nature. “Prejudices, passions, satanic attributes, have revealed themselves in men as they have exercised their powers against their fellow men.”21

_____________________________

Roy Branson was a Seventh-day Adventist theologian, social activist, ethicist, and educator. He was director of the Center for Christian Bioethics at Loma Linda University Health when he passed away in 2015. This article appeared in the April 16, 1970, Review and Herald. Used with permission.

1 Uriah Smith, editorial comment before "Letter to the President," Review and Herald 20, no. 17 (Sept. 23, 1862), p. 130.

2 Smith, editorial comment, p. 130.

3 Ellen G. White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 1 (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1885), p. 254.

4 James White, “Justice Awaking,” Review and Herald 23, no. 9 (Jan. 26, 1864), p. 68.

5 James White, “Justice Awaking,” p. 68.

6 Kenneth M. Stampp, The Era of Reconstruction, 1865-1877 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965), p. 16. Stampp is one of what is now the dominant school of Reconstruction historians called "revisionists." They have consciously attempted to correct earlier writers who interpreted Reconstruction as totally evil and oppressive.

7 Stampp, p. 105.

8 Stampp, p. 122.

9 Farrell Gilliland II, “Seventh-day Adventist Sentiment Toward Reconstruction After the Civil War" (unpublished manuscript, Andrews University, 1963).

10 Ellen G. White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 9 (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1909), p. 205.

11 Stampp, pp. 134-135.

12 Luther Lee, Slavery Examined in the Light of the Bible (Syracuse, NY: Wesleyan Methodist Book Room, 1855).

13 James White, "Thoughts on the Revelation," Review and Herald 20, no. 24 (Nov. 11, 1862), p. 188.

14 Uriah Smith, note before "The Degeneracy of the United States," Review and Herald 20, no. 3 (June 17, 1862), p. 22; cf. note before "The Cause and Cure of the Present Civil War," Review and Herald 20, no. 12 (Aug. 19, 1862), p. 89.

15 Ellen G. White, Spiritual Gifts, vol. 1 (Battle Creek, MI: Seventh-day Adventist Pub. Assn., 1858), p. 191.

16 Ellen G. White, Spiritual Gifts, pp. 192-193.

17 C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), p. 70; cf. Vincent P. DeSantis, Republicans Face the Southern Question (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1959), pp. 24-52.

18 Ellen G. White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 7 (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1902), p. 225.

19 Ellen G. White, Testimonies, vol. 7, p. 223.

20 Ellen G. White to J.E. and Emma White, Letter 80a, 1895 (Aug. 16, 1895).

21 Ellen G. White to J.E. and Emma White.

Where people's equality and freedom are violated, it is not God acting, but humanity's sinful nature.

Esclavitud y profecía

Por Roy Branson

Muchos líderes adventistas prominentes tenían puntos de vista sobre la esclavitud similares a los de la Sra. White. A lo largo de los años de la Guerra Civil, nombres tan venerados como James White, Uriah Smith y J. N. Andrews utilizaron las páginas de la Review and Herald para atacar a los rezagados que no apoyaban la posición de la emancipación. Un ejemplo es la crítica explícita de Uriah Smith al presidente Lincoln. Reconociendo tácitamente que su propia posición era radical, Smith censuró al presidente por «seguir su actual política conservadora, por no decir suicida».1 Con la emancipación aún no oficial, la hostilidad de Smith hacia Lincoln era implacable.

«Tiene que oponerse al “entusiasmo por la libertad” que reina en casi veinte millones de corazones en el Norte libre, y contra las oraciones de cuatro millones de esclavos oprimidos y sufrientes. Si continúa resistiéndose a todo eso, negándose a tomar las medidas que exigen una política sana, los principios de humanidad y la salvación del país, debe ser por un encaprichamiento similar al que en la antigüedad llevó a Faraón a un final prematuro».2 Smith no podía saber que el asesinato de Lincoln, en retrospectiva, haría que su analogía fuera francamente espeluznante.

Cuando el Norte estaba perdiendo batallas importantes, la Sra. White se quejó porque «la rebelión se manejaba con tanto cuidado, tan lentamente».3 Más tarde, cuando el Norte ganaba consistentemente, su esposo, James, escribió jubilosamente en la Review que «la retribución apropiada parece estar alcanzando por fin a las partes terriblemente culpables que durante largos años han mantenido en esclavitud a multitudes de sus semejantes».4

Al presentar un artículo noticioso reimpreso sobre las hazañas de los antiguos esclavos, ahora en el ejército de la Unión, que perseguían a los dueños de esclavos en los pantanos de Carolina del Norte, el pastor White preguntó: «¿Qué podría ser más apropiado que los esclavos mismos sean los instrumentos utilizados para castigar a los despiadados tiranos que durante tanto tiempo los han reducido al polvo?». Estaba convencido de que «la justicia, aunque parezca largamente retrasada, sigue sin embargo con pasos implacables al opresor».5

A la vanguardia de la Reconstrucción

Después de la guerra, los antiguos abolicionistas estuvieron a la vanguardia de la Reconstrucción. Hombres como Thaddeus Stevens en la Cámara de Representantes, Charles Sumner y Benjamin Wade en el Senado, y Edwin Stanton en el Gabinete llegaron a ser conocidos como republicanos radicales porque «parecían empeñados en diseñar una reforma radical de la sociedad sureña».6

Una historia reciente de la época insiste en que el idealismo fue parte de la motivación de la Reconstrucción y que «un deseo genuino de hacer justicia al negro, entonces, fue uno de los impulsos primarios del radicalismo».7 Los senadores y congresistas radicales lideraron la aprobación de leyes de derechos civiles para garantizar que los negros pudieran votar y disfrutar de plenas libertades civiles. Algunos radicales fueron más allá. «Creían que sería esencial dar a los negros no sólo derechos civiles y políticos, sino también alguna ayuda económica inicial».8

Es interesante notar que durante el apogeo de la Reconstrucción, 1867-1877, las citas en la Review concernientes a los asuntos nacionales parecen haber sido tomadas exclusivamente de publicaciones republicanas radicales y bien conocidas. El intento de destituir al presidente Andrew Johnson fue reportado en detalle.9

Más significativamente, cuando la Sra. White se dirigió más tarde a las necesidades del sur, lamentó la avaricia y la brevedad de la preocupación del gobierno por el hombre negro emancipado. Apoyó las ideas humanitarias del ala más progresista de los republicanos radicales, aquellos que sentían la obligación de ayudar al hombre negro política, legal y económicamente.

«El pueblo de América podría haber logrado mucho si el gobierno y las iglesias cristianas hubieran hecho esfuerzos adecuados en favor de los libertos inmediatamente después de la emancipación de los esclavos. El dinero debería haberse utilizado libremente para cuidarlos y educarlos en el momento en que tanto necesitaban ayuda. Pero el Gobierno, después de un pequeño esfuerzo, dejó que el negro luchara, sin ayuda, con su carga de dificultades».10

Indudablemente, el «pequeño esfuerzo» que la Sra. White elogió tuvo lugar durante el breve período de 1867 a 1877 cuando los gobiernos de la Reconstrucción incluyeron a negros, y se lograron algunas mejoras en la educación, la atención médica y su bienestar. También es posible que se haya referido a las actividades de la Oficina de Libertos. Organizada y financiada por un gobierno federal dominado por radicales, funcionó sólo durante cuatro años, hasta 1869. Durante ese tiempo, la oficina brindó atención médica a un millón de personas, gastó $5 millones en escuelas para negros, supervisó los contratos laborales de los trabajadores negros y administró tribunales especiales para proteger los derechos civiles de los libertos.11 La Sra. White consideró que se debería haber hecho más, pero la Reconstrucción terminó demasiado pronto para que los radicales llevaran a cabo sus reformas radicales.

Poco más de una década después de la Guerra Civil, ocho de los estados sureños habían votado para destituir a los líderes políticos que apoyaban políticas republicanas radicales. En las elecciones de 1876, los demócratas se adjudicaron la victoria en los tres estados restantes de la Confederación: Carolina del Sur, Florida y Luisiana. En la primavera del año siguiente, el presidente Rutherford B. Hayes retiró las últimas tropas federales del sur. La Reconstrucción había terminado. La coalición republicana de negros, carpetbaggers [oportunistas] del norte y tránsfugas blancos del sur había perdido su dominio. Los sureños llamaron a la nueva era «Redención».

Algunas comparaciones persistentes entre la Sra. White (y otros escritores adventistas) y los abolicionistas y republicanos radicales pueden dejar la impresión de que los adventistas simplemente adoptaron el punto de vista sobre los problemas nacionales que encontraban a su alrededor, que su religión tenía poco que ver con sus puntos de vista sobre temas sociales y morales. Pero nada está más lejos de la realidad. Si alguien les hubiera dicho a los padres fundadores de nuestra denominación que sus actitudes hacia la raza no tenían nada que ver con su teología, habrían sacudido la cabeza con incredulidad. Para Ellen y James White, Uriah Smith y J. N. Andrews, las actitudes apropiadas hacia las relaciones raciales eran parte de una verdadera comprensión de la Biblia y sus doctrinas.

Esclavitud y profecía

La emancipación fue un hecho oficial el 1 de enero de 1863. Durante los próximos tres meses, 12 números de la Review comenzaron con extractos de primera plana de la obra de Luther Lee, La esclavitud examinada a la luz de la Biblia.12 El libro repasó textos controvertidos del Antiguo y el Nuevo Testamento, argumentando enérgicamente que la Biblia, lejos de condonar la esclavitud, la condenaba.

«Cuando las leyes de los hombres entran en conflicto con la Palabra y la ley de Dios, hemos de obedecer a estas últimas, cualesquiera que sean las consecuencias. No hemos de obedecer la ley de nuestro país que exige la entrega de un esclavo a su amo; y debemos soportar las consecuencias de su violación. El esclavo no es propiedad de hombre alguno. Dios es su legítimo dueño, y el hombre no tiene derecho de apoderarse de la obra de Dios y llamarla suya»

Tanto Uriah Smith como James White relacionaron la esclavitud con la profecía. Así como los Estados Unidos estaban divididos en dos bandos, así el cordero en Apocalipsis 13:11 tenía dos cuernos. La opresión de los negros en Estados Unidos fue una evidencia más significativa de que la bestia en Apocalipsis 13 era Estados Unidos. Apocalipsis describe a una bestia que se parece a un cordero pero habla como un dragón. James White hizo esa aplicación.

«Su apariencia externa y profesión [de los Estados Unidos] es la más pura, pacífica e inofensiva posible. Profesa garantizar a cada hombre la libertad y la búsqueda de la felicidad en las cosas temporales, y la libertad en materia de religión; sin embargo, cerca de cuatro millones de seres humanos están sometidos por los estados del sur de esta nación en la más abyecta y cruel esclavitud y servidumbre, y los cuerpos teológicos del país han adoptado un poder de credo que es tan inexorable y tiránico como es posible ejercer sobre las conciencias de los hombres. Verdaderamente, con toda su apariencia y profesión de cordero, tiene el corazón y la voz de un dragón; porque de la abundancia del corazón habla la boca».13

Uriah Smith señaló la «villanía blanqueada de muchos de los púlpitos de nuestra tierra», los púlpitos que apoyaban la esclavitud, evidencia de que «el espíritu dragonial de esta nación se ha desarrollado en los últimos años de acuerdo con la profecía de Apocalipsis 13, 11».14 Lejos de ser una preocupación puramente secular, los adventistas pensaban que las relaciones raciales estaban íntimamente relacionadas con una comprensión adecuada de la profecía y los acontecimientos de los últimos días.

La Sra. White también vio a la esclavitud como una de las señales de los tiempos. Citó la defensa de la esclavitud por parte de las instituciones eclesiásticas como prueba de que las iglesias en América eran parte de la Babilonia apóstata. «Dios contendrá su ira, pero por un poco más. Su ira arde contra esta nación, y especialmente contra los cuerpos religiosos que han sancionado y se han dedicado a esa terrible mercancía».15 Dios recordará al esclavo que sufre y a otros que están oprimidos. «Los nombres de los tales están escritos con sangre, tachados de azotes e inundados de lágrimas agonizantes y ardientes de sufrimiento. La ira de Dios no cesará hasta que haya hecho que la tierra de luz beba las heces del cáliz de su furia, y hasta que haya recompensado a Babilonia el doble... Todos los pecados del esclavo serán colocados sobre el amo».16

Habría sido posible que los adventistas se hubieran opuesto a la esclavitud, que vieran su maldad como una de las señales del fin, y que aun así no predicaran la igualdad entre negros y blancos. En la época del colapso de la Reconstrucción y el nacimiento de la Redención, cuando la Sra. White lanzó sus llamados a la obra del sur, incluso los periódicos republicanos radicales asumieron la inferioridad del hombre negro. «Era bastante común en los años ochenta y noventa encontrar en los años ochenta y noventa en Nation, Harper’s Weekly, el North American Review, o el Atlantic Monthly a los liberales del norte y los exabolicionistas que pronunciaban los estereotipos de la supremacía blanca con respecto a la inferioridad innata del negro, su indiferencia y su ineptitud desesperada para participar plenamente en la civilización del hombre blanco».17 Durante ese mismo período de los años ochenta y noventa, la Sra. White fue inflexible: los negros y los blancos son iguales.

Además de la escatología, o el estudio de los acontecimientos de los últimos días, la Sra. White basó su análisis de la raza en otras dos doctrinas: la redención y la creación. La obra expiatoria y reconciliadora de Cristo significaba que todos los hombres se salvaran, y ninguno se salvaría más que los demás: «Cristo vino a esta tierra con un mensaje de misericordia y perdón. Sentó las bases para una religión por la cual judíos y gentiles, blancos y negros, libres y esclavos, están unidos en una hermandad común, reconocida como igual a los ojos de Dios».18 Para la Sra. White, Cristo había llevado a los seres humanos a una nueva relación en la que cada uno estaba igualmente relacionado con él. Los cristianos, por lo tanto, deberían mirar a los demás cristianos como iguales.

Pero, ¿qué pasa con los que no eran cristianos? Si los hombres no se convirtieran, si no estuvieran dentro de la hermandad creada por la vida redentora de Cristo, ¿podrían relacionarse adecuadamente como superiores a inferiores, como amo a esclavo? «No», fue la respuesta enfática de la Sra. White. La doctrina de la Creación lo impide. Dios quiere que los blancos que se relacionan con las personas negras recuerden «su relación común con nosotros por la creación y por la redención, y su derecho a las bendiciones de la libertad».19 En otro lugar insistió en que «el hombre es propiedad de Dios por creación y redención».20

Es significativo que la Sra. White no apoyara la igualdad simplemente sobre la base de la redención. Incluso si los hombres no estuvieran convertidos, la doctrina de la Creación significa que todos los seres humanos, ya sea que reconozcan a Cristo o no, pertenecen a Dios. Cuando se viola la igualdad y la libertad de las personas, no es Dios el que actúa, sino la naturaleza pecaminosa de la humanidad. «Los prejuicios, las pasiones, los atributos satánicos, se han revelado en los hombres a medida que han ejercido sus poderes contra sus semejantes».21

_____________________________

Roy Branson fue un teólogo, activista social, especialista en ética y educador de la Iglesia Adventista del Séptimo Día. Era director del Centro de Bioética Cristiana de la Loma Linda University Health cuando falleció en 2015. Este artículo apareció en la revista Review and Herald del 16 de abril de 1970. Usado con permiso.

1 Uriah Smith, comentario editorial antes de “Letter to the President,” Review and Herald 20, no. 17 (Sept. 23, 1862), p. 130.

2 Smith, comentario editorial, p. 130.

3 Ellen G. White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 1 (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1885), p. 254.

4 James White, «Justice Awaking,» Review and Herald 23, no. 9 (Jan. 26, 1864), p. 68.

5 James White, «Justice Awaking,» p. 68.

6 Kenneth M. Stampp, The Era of Reconstruction, 1865-1877 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965), p. 16. Stampp pertenece a lo que ahora es la escuela dominante de historiadores de la Reconstrucción llamados “revisionistas”. Han intentado conscientemente corregir a los escritores anteriores que interpretaron la Reconstrucción como totalmente malvada y opresiva

7 Stampp, p. 105.

8 Stampp, p. 122.

9 Farrell Gilliland II, “Seventh-day Adventist Sentiment Toward Reconstruction After the Civil War” (manuscrito inédito, Andrews University, 1963).

10 Ellen G. White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 9 (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1909), p. 205.

11 Stampp, pp. 134-135.

12 Luther Lee, Slavery Examined in the Light of the Bible (Syracuse, NY: Wesleyan Methodist Book Room, 1855).

13 James White, "Thoughts on the Revelation," Review and Herald 20, no. 24 (Nov. 11, 1862), p. 188.

14 Uriah Smith, nota antes de “The Degeneracy of the United States,” Review and Herald 20, no. 3 (June 17, 1862), p. 22; cf. nota antes de “The Cause and Cure of the Present Civil War,” Review and Herald 20, no. 12 (Aug. 19, 1862), p. 89.

15 Ellen G. White, Spiritual Gifts, vol. 1 (Battle Creek, MI: Seventh-day Adventist Pub. Assn., 1858), p. 191.

16 Ellen G. White, Spiritual Gifts, pp. 192-193.

17 C. Vann Woodward, The Strange Career of Jim Crow (New York: Oxford University Press, 1966), p. 70; cf. Vincent P. DeSantis, Republicans Face the Southern Question (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1959), pp. 24-52.

18 Ellen G. White, Testimonies for the Church, vol. 7 (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press Pub. Assn., 1902), p. 225.

19 Ellen G. White, Testimonies, vol. 7, p. 223.

20 Ellen G. White a J.E. y Emma White, Letter 80a, 1895 (Aug. 16, 1895).

21 Ellen G. White a J.E. y Emma White.